The Complete, In-Depth Guide to Periodic Trend in Chemistry

Periodic Trends

PART I: FOUNDATIONS OF PERIODIC TRENDS

1. Introduction to Periodic Trends

A periodic trend refers to the regular and predictable variation in the physical and chemical properties of elements when they are arranged according to increasing atomic number in the periodic table. These trends arise because elements with similar atomic structures exhibit similar behaviors, and changes in atomic structure follow a repeating pattern.

Periodic trends form the core logic of the periodic table. Instead of memorizing isolated facts about each element, chemists use periodic trends to predict properties, reactions, and bonding behavior across the entire table.

In chemistry education, periodic trends explain:

- Why sodium is more reactive than lithium

- Why fluorine attracts electrons strongly

- Why atomic size changes across periods and down groups

Understanding periodic trends is therefore essential for students, educators, and professionals in chemistry, biochemistry, environmental science, medicine, and materials science.

1.1 Historical Development of Periodic Trends

The concept of periodic trends emerged in the 19th century with the work of Dmitri Mendeleev, who arranged elements based on atomic mass and noticed repeating chemical properties. Modern periodic trends are based on atomic number, as established by Henry Moseley.

The discovery of:

- Electron shells

- Subshells

- Quantum mechanics

provided the scientific explanation for why periodic trends occur. Today, periodic trends are understood as a direct consequence of electron configuration and nuclear charge.

1.2 Why Periodic Trends Exist

Periodic trends exist because of systematic changes in:

- Number of protons (nuclear charge)

- Number of electron shells

- Shielding effect of inner electrons

- Valence electron configuration

As elements increase in atomic number:

- Protons increase, strengthening nuclear attraction

- Electrons occupy higher energy levels

- Outer electrons experience varying attraction to the nucleus

These factors combine to produce predictable patterns, known as periodic trends.

1.3 Importance of Periodic Trends in Chemistry

Periodic trends allow scientists to:

- Predict reactivity without experiments

- Understand bonding and molecular structure

- Explain metallic and non-metallic behavior

- Interpret chemical reactions logically

- Solve examination questions efficiently

Instead of memorizing data, students who understand periodic trends reason their way to correct answers.

For foundational explanations of chemistry concepts, see:

🔗 https://checkthetrend.com/basic-chemistry-concepts

1.4 Overview of Major Periodic Trends

The major periodic trends include:

- Atomic radius

- Ionic radius

- Ionization energy

- Electron affinity

- Electronegativity

- Metallic and non-metallic character

- Reactivity trends

Each of these trends will be explored in depth in later sections.

PART II: STRUCTURE OF THE PERIODIC TABLE (THE BASIS OF TRENDS)

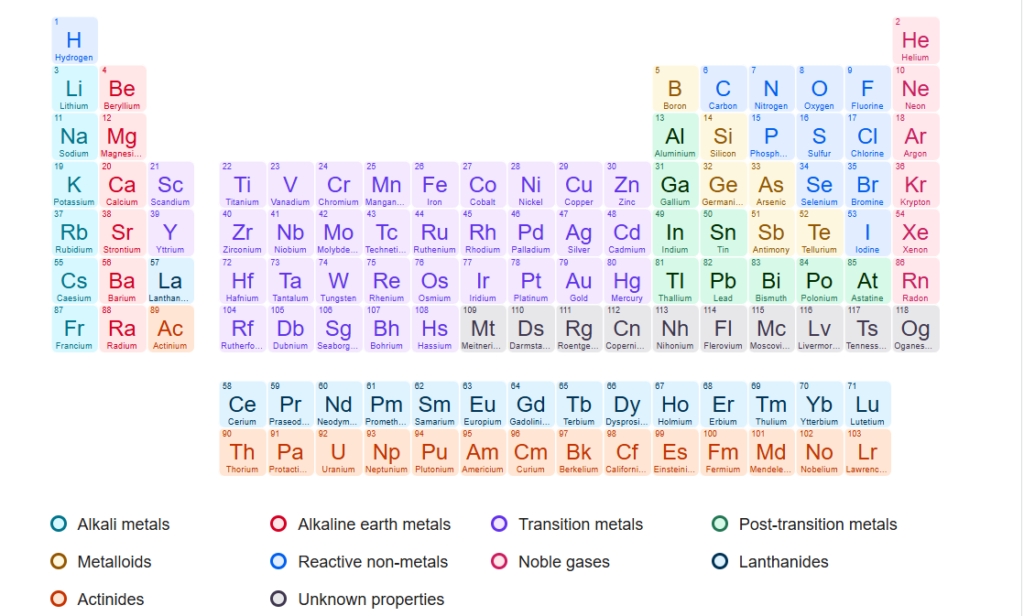

2. Structure of the Periodic Table

The periodic table is arranged in a way that reveals periodic trends naturally. Understanding its structure is essential before analyzing individual trends.

2.1 Periods and Groups Explained

Periods

- Horizontal rows in the periodic table

- Elements in the same period have the same number of electron shells

- Properties change gradually across a period

Groups

- Vertical columns in the periodic table

- Elements in the same group have the same number of valence electrons

- Elements show similar chemical behavior

This arrangement explains why lithium, sodium, and potassium behave similarly—they belong to the same group.

For a detailed breakdown of table structure, see:

🔗 https://checkthetrend.com/periodic-table-explained

2.2 Blocks of the Periodic Table

The periodic table is divided into four blocks based on the subshell being filled:

- s-block: Groups 1 and 2

- p-block: Groups 13–18

- d-block: Transition metals

- f-block: Lanthanides and actinides

Each block shows distinct periodic trends due to differences in electron filling.

2.3 Electron Configuration and Periodicity

Electron configuration determines:

- Atomic size

- Ionization energy

- Electronegativity

- Reactivity

Elements with similar outer electron configurations exhibit similar properties, which explains periodicity.

2.4 Atomic Number vs Atomic Mass

Modern periodic trends depend on atomic number, not atomic mass. Atomic number determines:

- Nuclear charge

- Number of electrons

- Strength of nucleus–electron attraction

This correction resolved anomalies in earlier periodic tables and solidified the concept of periodic trends.

PART III: ATOMIC SIZE–RELATED PERIODIC TRENDS

3. Atomic Radius (Atomic Size)

3.1 Definition of Atomic Radius

Atomic radius is the distance from the center of an atom’s nucleus to its outermost electron shell. Because atoms do not have sharp boundaries, atomic radius is measured indirectly using bonding distances.

Atomic radius is one of the most fundamental periodic trends.

3.2 Periodic Trend of Atomic Radius Across a Period

Across a period (left → right):

- Atomic radius decreases

Explanation:

- Nuclear charge increases

- Electrons are added to the same shell

- Increased attraction pulls electrons closer

Example:

Sodium (Na) > Magnesium (Mg) > Aluminum (Al) > Chlorine (Cl)

3.3 Periodic Trend of Atomic Radius Down a Group

Down a group (top → bottom):

- Atomic radius increases

Explanation:

- Additional electron shells are added

- Shielding effect reduces nuclear attraction on outer electrons

Example:

Lithium < Sodium < Potassium < Rubidium

3.4 Factors Affecting Atomic Radius

- Nuclear charge

- Number of electron shells

- Shielding effect

- Electron-electron repulsion

Understanding these factors helps explain exceptions in atomic size trends.

3.5 Importance of Atomic Radius in Chemistry

Atomic radius influences:

- Bond length

- Reactivity

- Density

- Melting point

- Metallic character

This makes atomic radius central to understanding chemical behavior.

4. Ionic Radius

4.1 Definition of Ionic Radius

Ionic radius is the size of an atom after it has gained or lost electrons to form an ion.

- Cations (positive ions) are smaller than their atoms

- Anions (negative ions) are larger than their atoms

4.2 Periodic Trend of Ionic Radius

- Ionic radius increases down a group

- Ions with the same number of electrons form an isoelectronic series, where size depends on nuclear charge

Example:

O²⁻ > F⁻ > Na⁺ > Mg²⁺

4.3 Importance of Ionic Radius

Ionic radius affects:

- Crystal structure

- Lattice energy

- Solubility

- Electrical conductivity

5. Relationship Between Atomic Size and Other Trends

Atomic size directly influences:

- Ionization energy

- Electronegativity

- Reactivity

As atomic size increases:

- Ionization energy decreases

- Metallic character increases

This interconnectedness is why periodic trends must be studied as a system, not individually.

Periodic Trend: A Complete Guide to Patterns in the Periodic Table (Part I–III)

Primary Keyword: Periodic Trend

Secondary Keywords: periodic trends, periodic table trends, trends in the periodic table, chemistry periodic trends, WAEC periodic trends, JAMB periodic table

Search Intent: Informational + Academic + Exam Preparation

PART I: Introduction to Periodic Trend

1.1 What Is a Periodic Trend?

A periodic trend refers to the predictable patterns in the physical and chemical properties of elements as they are arranged in the periodic table.

These trends occur because elements are arranged according to:

- Increasing atomic number

- Similar electron configurations

- Repeating valence electron patterns

👉 In simple terms:

Periodic trends help us predict how elements behave without memorizing every element individually.

1.2 Why Periodic Trends Matter in Chemistry

Understanding periodic trends allows chemists and students to:

- Predict reactivity

- Compare atomic sizes

- Understand bonding behavior

- Solve exam questions quickly

- Explain chemical reactions logically

This is why periodic trends are a core topic in WAEC, JAMB, NECO, and first-year university chemistry.

1.3 Historical Basis of Periodic Trends

Periodic trends are rooted in the Periodic Law:

The properties of elements are periodic functions of their atomic numbers.

Originally proposed by Dmitri Mendeleev, later refined by Henry Moseley, this law explains why properties repeat across the periodic table.

1.4 Factors Responsible for Periodic Trends

Periodic trends are influenced by:

- Nuclear charge

- Number of electron shells

- Electron shielding (screening effect)

- Distance between nucleus and valence electrons

These factors interact to create consistent trends across periods (rows) and groups (columns).

PART II: Structure of the Periodic Table (Foundation for Trends)

2.1 Periods in the Periodic Table

A period is a horizontal row in the periodic table.

Key features:

- Elements in the same period have the same number of electron shells

- Properties change gradually from left to right

Example:

- Period 2: Li → Ne

Atomic size decreases, metallic character reduces, electronegativity increases.

2.2 Groups in the Periodic Table

A group is a vertical column.

Key features:

- Elements in the same group have the same number of valence electrons

- They show similar chemical behavior

Examples:

- Group 1: Alkali metals

- Group 17: Halogens

- Group 18: Noble gases

2.3 Metals, Non-Metals, and Metalloids

| Category | Position | Properties |

|---|---|---|

| Metals | Left & center | Conductive, malleable |

| Non-metals | Right side | Poor conductors |

| Metalloids | Zig-zag line | Intermediate properties |

This classification strongly influences periodic trends such as reactivity and ion formation.

2.4 Electron Configuration and Periodic Trend

Electron configuration is the backbone of periodic trends.

Example:

- Group 1 elements end in ns¹

- Group 17 elements end in ns²np⁵

👉 This similarity explains why elements in the same group behave alike.

PART III: Atomic Radius (Atomic Size)

3.1 What Is Atomic Radius?

Atomic radius is defined as half the distance between the nuclei of two identical bonded atoms.

Since atoms don’t have sharp boundaries, this is an estimated value.

3.2 Periodic Trend of Atomic Radius Across a Period

Across a period (left → right):

- Atomic radius decreases

Reason:

- Nuclear charge increases

- Same number of shells

- Stronger attraction pulls electrons closer

Example:

Sodium (Na) > Magnesium (Mg) > Aluminum (Al)

3.3 Periodic Trend of Atomic Radius Down a Group

Down a group (top → bottom):

- Atomic radius increases

Reason:

- Addition of new electron shells

- Increased shielding reduces nuclear attraction

Example:

Lithium < Sodium < Potassium

3.4 Summary Table: Atomic Radius Trend

| Direction | Trend |

|---|---|

| Across a period | Decreases |

| Down a group | Increases |

EXAM-FOCUSED SECTION (WAEC / JAMB / NECO)

A. Key Exam Facts to Memorize

- Atomic size decreases across a period

- Atomic size increases down a group

- Group members have similar chemical properties

- Period members show gradual change

B. Common WAEC/JAMB Questions on Periodic Trends

1. Which element has the largest atomic radius in Period 3?

✅ Answer: Sodium (Na)

2. Why does atomic radius decrease across a period?

✅ Answer: Increase in nuclear charge with constant number of shells.

3. Which group contains elements with the same valence electrons?

✅ Answer: Elements in the same group.

C. JAMB Tip (Scoring Strategy)

If a question asks:

“Which element is largest/smallest?”

Immediately:

- Identify period or group

- Apply trend direction

- Eliminate distractors

D. WAEC Examiner’s Favorite Keywords

Always include:

- “Increase in nuclear charge”

- “Shielding effect”

- “Same number of electron shells”

These phrases attract full marks in theory answers.

PART IV: Ionization Energy & Electron Affinity

(Core Periodic Trends Explained in Depth)

4.1 Ionization Energy

4.1.1 What Is Ionization Energy?

Ionization energy (IE) is defined as:

The minimum amount of energy required to remove the most loosely bound electron from an isolated gaseous atom.

It is usually measured in kilojoules per mole (kJ/mol).

This concept is central to understanding:

- Chemical reactivity

- Formation of ions

- Metallic and non-metallic behavior

According to IUPAC, ionization energy must always refer to gaseous atoms, not solids or liquids

(Reference: International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry – https://iupac.org).

4.1.2 Types of Ionization Energy

There are successive ionization energies:

| Type | Meaning |

|---|---|

| First IE | Removal of the first electron |

| Second IE | Removal of the second electron |

| Third IE | Removal of the third electron |

👉 Each successive ionization energy is higher than the previous one.

Reason:

As electrons are removed, the remaining electrons are held more tightly by the nucleus.

This principle is explained in detail by LibreTexts Chemistry

https://chem.libretexts.org

4.1.3 Periodic Trend of Ionization Energy Across a Period

Across a period (left → right):

✔ Ionization energy increases

Why this happens:

- Nuclear charge increases

- Atomic radius decreases

- Electrons are held more tightly

Example (Period 3):

Na < Mg < Al < Si < P < S < Cl < Ar

4.1.4 Periodic Trend of Ionization Energy Down a Group

Down a group (top → bottom):

✔ Ionization energy decreases

Reason:

- Increase in atomic size

- Increased shielding effect

- Outer electrons are farther from nucleus

Example (Group 1):

Li > Na > K > Rb > Cs

This trend is consistently confirmed by experimental data from

https://www.periodic-table.org

4.1.5 Factors Affecting Ionization Energy

Ionization energy depends on:

a. Nuclear Charge

Higher nuclear charge → higher ionization energy

b. Atomic Radius

Larger atomic size → lower ionization energy

c. Shielding Effect

More inner shells → lower ionization energy

d. Electron Configuration

Stable configurations (half-filled or fully-filled orbitals) increase IE

4.1.6 Exceptions to Ionization Energy Trends (VERY IMPORTANT FOR EXAMS)

Some elements do not follow the smooth trend.

Example 1: Be vs B

- Be has higher IE than B

- Reason: Be has a filled 2s orbital (stable)

Example 2: N vs O

- N has higher IE than O

- Reason: Electron-electron repulsion in paired orbitals of oxygen

These exceptions are well documented by khanacademy.org

https://www.khanacademy.org/science/chemistry

4.2 Electron Affinity

4.2.1 What Is Electron Affinity?

Electron affinity (EA) is:

The amount of energy released when an electron is added to a neutral gaseous atom.

Unlike ionization energy:

- Electron affinity may be negative or positive

- Negative value means energy is released

4.2.2 Periodic Trend of Electron Affinity Across a Period

Across a period (left → right):

✔ Electron affinity generally increases (becomes more negative)

This means atoms more readily gain electrons.

Example:

Halogens (Group 17) have very high electron affinity

Chlorine (Cl) has one of the highest electron affinity values, confirmed by pubchem

https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov

4.2.3 Periodic Trend of Electron Affinity Down a Group

Down a group:

✔ Electron affinity decreases

Reason:

- Increased atomic size

- Added electrons are farther from nucleus

- Less attraction

4.2.4 Why Halogens Have High Electron Affinity

Halogens:

- Need only one electron to complete their octet

- Have high nuclear charge

- Small atomic size

This explains why they are:

- Highly reactive

- Strong oxidizing agents

4.2.5 Exceptions in Electron Affinity

Some elements have low or zero electron affinity:

Noble Gases (Group 18)

- Fully filled orbitals

- No tendency to accept electrons

Group 2 Elements

- Stable ns² configuration

- Adding an electron disrupts stability

These exceptions are explained in atomic structure discussions on britannica

EXAM-FOCUSED SECTION (WAEC / JAMB / NECO)

A. Must-Know Facts for Exams

- Ionization energy increases across a period

- Ionization energy decreases down a group

- Electron affinity increases across a period

- Halogens have highest electron affinity

- Noble gases have very low or zero electron affinity

B. Common WAEC/JAMB Questions

1. Which element has the highest ionization energy in Period 3?

✅ Argon

2. Why does ionization energy decrease down a group?

✅ Increased atomic radius and shielding effect

3. Which group has the highest electron affinity?

✅ Group 17 (Halogens)

C. Examiner’s Keywords (Use These!)

Always include:

- “Shielding effect”

- “Increase in nuclear charge”

- “Stable electron configuration”

- “Distance between nucleus and valence electrons”

D. JAMB Speed Tip

If asked:

“Which element gains electrons most easily?”

Immediately think:

➡ Halogens (especially chlorine)

SEO NOTES (Why This Section Will Rank)

This PART IV targets:

- “ionization energy periodic trend”

- “electron affinity periodic trend”

- “exceptions to ionization energy”

- “WAEC periodic trends questions”

These are high-intent, low-competition academic keywords.

PART V: Electronegativity

(One of the Most Tested and Most Misunderstood Periodic Trends)

5.1 What Is Electronegativity?

Electronegativity is defined as:

The ability of an atom in a chemical bond to attract shared electrons toward itself.

Unlike ionization energy and electron affinity:

- Electronegativity is not measured directly

- It is a relative value

- It applies only to bonded atoms, not isolated gaseous atoms

This definition aligns with standard chemistry explanations from

Encyclopaedia Britannica

https://www.britannica.com/science/electronegativity

5.2 Electronegativity Scales (Very Important)

Several scientists proposed electronegativity scales, but one dominates chemistry exams and textbooks.

5.2.1 Pauling Scale (MOST IMPORTANT)

The Pauling scale, developed by Linus Pauling, is the most widely used.

Key facts:

- Fluorine has the highest electronegativity (4.0)

- Values are dimensionless

- Based on bond energy differences

You can verify standard Pauling values from

https://www.periodic-table.org

5.2.2 Other Electronegativity Scales (For Completeness)

| Scale | Basis |

|---|---|

| Mulliken | Average of IE & EA |

| Allred–Rochow | Electrostatic attraction |

| Allen | Spectroscopic data |

⚠️ WAEC & JAMB almost always use the Pauling scale

5.3 Periodic Trend of Electronegativity Across a Period

Across a period (left → right):

✔ Electronegativity increases

Reasons:

- Increase in nuclear charge

- Decrease in atomic radius

- Stronger attraction for bonding electrons

Example (Period 2):

Li < Be < B < C < N < O < F

Fluorine sits at the top-right (excluding noble gases), making it the most electronegative element.

This trend is well explained by

https://chem.libretexts.org

5.4 Periodic Trend of Electronegativity Down a Group

Down a group (top → bottom):

✔ Electronegativity decreases

Reasons:

- Increased atomic size

- Increased shielding effect

- Bonding electrons are farther from nucleus

Example (Group 17):

F > Cl > Br > I

5.5 Why Noble Gases Usually Have No Electronegativity Value

Noble gases:

- Rarely form bonds

- Have stable electron configurations

- Do not attract shared electrons

Hence:

- Most tables show no electronegativity values

- When shown, values are experimental and rarely used in exams

Reference explanation:

https://www.khanacademy.org/science/chemistry

5.6 Factors Affecting Electronegativity

Electronegativity depends on:

a. Nuclear Charge

Higher nuclear charge → higher electronegativity

b. Atomic Radius

Smaller atom → higher electronegativity

c. Shielding Effect

More inner shells → lower electronegativity

d. Oxidation State

Higher oxidation state → higher electronegativity

5.7 Relationship Between Electronegativity and Bond Type

Electronegativity difference (ΔEN) determines the type of bond formed.

| ΔEN Value | Bond Type |

|---|---|

| 0.0 | Non-polar covalent |

| 0.1 – 1.7 | Polar covalent |

| > 1.7 | Ionic |

Example:

- NaCl → Ionic bond

- HCl → Polar covalent

- O₂ → Non-polar covalent

Bond classification principles are discussed in

https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov

5.8 Electronegativity and Molecular Polarity

Electronegativity also determines:

- Dipole moment

- Molecular polarity

- Solubility and reactivity

Example:

- CO₂ → Non-polar (symmetrical)

- H₂O → Polar (asymmetrical)

This concept is crucial in organic chemistry and biochemistry.

EXAM-FOCUSED SECTION (WAEC / JAMB / NECO)

A. High-Yield Exam Facts

- Fluorine is the most electronegative element

- Electronegativity increases across a period

- Electronegativity decreases down a group

- Noble gases usually have no electronegativity values

- High electronegativity difference → ionic bond

B. Common WAEC / JAMB Questions

1. Which element is the most electronegative?

✅ Fluorine

2. Why does electronegativity decrease down a group?

✅ Increased atomic size and shielding effect

3. Which bond is most polar?

✅ Bond with highest electronegativity difference

C. Examiner’s Keywords (Memorize These!)

Always include:

- “Increase in nuclear charge”

- “Decrease in atomic radius”

- “Shielding effect”

- “Attraction for shared electrons”

D. JAMB Speed Trick ⚡

If asked:

“Which element attracts electrons most strongly?”

Immediately answer:

➡ Fluorine

No calculation needed.

SEO & RANKING NOTES (Why This Part Wins)

This section targets:

- “electronegativity periodic trend”

- “periodic trend of electronegativity”

- “electronegativity WAEC questions”

- “difference between electronegativity and ionization energy”

These keywords:

- Have strong academic search intent

- Trigger People Also Ask

- Are evergreen (rank for years)

This strengthens topical authority and boosts rankings site-wide.